In my previous post, I talked about how Microsoft’s TypeScript was able to build simple class-based inheritance on top of JavaScript’s prototypal inheritance. To recap, the compiler includes a short function named extends that handles rejigging the prototype chain between the sub-class and the super-class to achieve the desired inheritance.

[javascript]

var __extends = this.__extends || function (d, b) {

for (var p in b) if (b.hasOwnProperty(p)) d[p] = b[p];

function __() { this.constructor = d; }

__.prototype = b.prototype;

d.prototype = new __();

};

[/javascript]

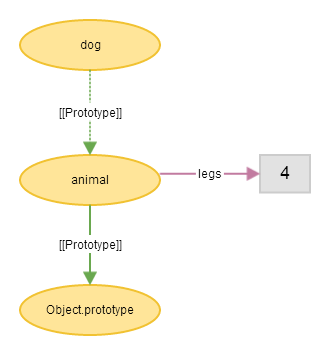

The trickiness of this pattern can help us understand the impetus for one of JavaScript’s newer features, Object.create. When you first encounter this method, you might wonder why JavaScript needs another way to create objects, when it already has the object literal syntax and constructor functions? Where Object.create differs from those options is that lets you provide, as the first argument to the method, an object that will become the new object’s prototype.

Remember that there is a difference between an object’s public prototype property and its internal [[Prototype]] property. When JavaScript is looking up properties on an object, it uses the latter, but traditionally the only standardised way to control it for a new object has been to use the pattern applied by __extends. You create a new function with a public prototype property, then apply the new operator on the function to create a new object. When the new operator is used with a function, the runtime sets the [[Prototype]] property of the new object to the object referenced by the public prototype property of the function.

While this approach to controlling the [[Prototype]] works, it is a little opaque and wasteful, requiring the declaration of a new function simply for the purpose of controlling this internal property. With Object.create, the extra function is no longer required, as the [[Prototype]] can be controlled directly. A dead simple example would be.

[javascript]

var animal = {

legs: 4

},

dog;

dog = Object.create(animal);

dog.legs == 4; // True

[/javascript]

The end result couldn’t be simpler — An object dog with a [[Prototype]] of animal.

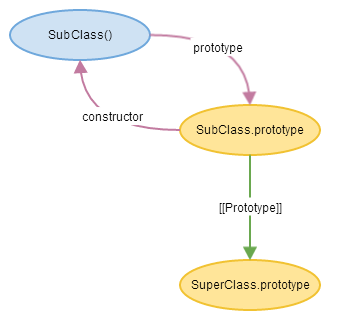

We can extend this to reproduce the functionality of __extends without the faff of an additional function.

[javascript]

function SuperClass() { };

function SubClass() { };

SubClass.prototype = Object.create(SuperClass.prototype);

SubClass.prototype.constructor = SubClass;

[/javascript]

I think you’ll agree that this is a much friendlier pattern than what __extends does, and in fact only today I found it recommended in feedback from the W3C TAG to the Web Audio working group, referred to as the “subclassing pattern”. So why didn’t Microsoft use it? Unfortunately, Object.create isn’t supported in Internet Explorer 8 and below, meaning TypeScript has to use the older pattern in order to maximise compatibility. Since __extends is compiler-generated JavaScript, its readability hardly matters anyway, as TypeScript developers will only see the class syntax of that language.

__proto__

I said above that there was traditionally no standardised way to control an object’s [[Prototype]]. However, some browsers have long supported a way of accessing and even changing it, through the __proto__ property. Although not part of any official specification, this property became a de facto standard, and gained support in all the major browsers except IE. It seems this property was controversial, as it was considered an abstraction error, and mutable prototypes were argued to cause implementation problems. There was talk of deprecating and eventually removing __proto__, while standardising equivalent capability, first through the introduction of Object.create and Object.getPrototypeOf in EcmaScript 5 and now Object.setPrototypeOf in EcmaScript 6 ((setPrototypeOf seems locked-in for ES6, despite Brendan Eich saying in 2011 that it wasn’t going to happen. Although it appears no browser has actually implemented it yet.)). But __proto__ has not gone away yet, and in fact it appears from pre-release builds that Internet Explorer 11 will support it, so who knows if it will ever really die.

Leave a Reply